I held off on writing any account of the Donetsk region for a few reasons.

For starters, I was there for just three days as a policy and process observer. I was kept as far from danger as one can be in the Kramatorsk region, during a run of quiet nights when all of Russia’s long range aerial attacks were directed at Kyiv (I felt both guilty and grateful for having missed those). So many soldiers, volunteers, and aid workers – to say nothing of actual residents – risk far more than I do for a cause we all believe in. Also, it would have made my parents worry.

Still, so few people even in Kyiv have an understanding or appreciation of the realities of Donetsk Oblast; it won’t hurt to share my impression. Besides – and with all understanding afforded to the ongoing effects of war – the food just isn’t great;* I’m not expecting to be back.

Kramatorsk, founded in 1868, is a new city by the standards of Ukraine and was primarily identified as a factory town that reached a peak population of 204,000 in 1993. Its industrial nature helped make it a hub for Bolshevism during the uprisings of the early 1900s, in line with the rest of the region. The city was taken in 2014 by Russian paramilitaries during the first phases of the war and held for three months before it was retaken by Ukrainian regulars. Putin is surely still cursing that reversal: Kramatorsk and the neighboring Sloviansk are the largest cities in Donetsk still held by Ukraine and are thus the strategic fortresses in the oblast.

It is over 100 degrees Fahrenheit when I arrive by train in July and there are few surviving businesses with air conditioning or bathrooms. The roads are filled with a caterpillar of smooth and steady traffic composed of both civilian and military vehicles, passing through the sunflower fields below an enormous sky that evoke the nation’s banner. Huge plumes of smoke rise from the military installations the Russians hit with ballistic missiles and FPV drones, visible across the wide open farmland.

I stay in an evacuated apartment with the medevac team. I am immensely grateful for the free roof over my head, but luxuries are few for volunteer crews this close to the front lines; the fact that this space boasts running water three days a week puts it well above what most people can get on donations. Most of the drywall is stripped and scarcely a window pane remains whole in this two bedroom walkup that houses do gooders with the highest standards of British and American education; some surfaces and doors still sport Lisa Frank-style decoration, evidence of the children that once lived here… the absurdity often outweighs the poignancy in these parts. The guys will be out all day in these sweltering conditions – absent air conditioning even in the vehicles – and when they get back to Bravo House they typically just collapse on sunken mattresses with minimal conversation. Booze being a banned substance in Donetsk these days (not that any can’t be smuggled in), there’s not a whole lot to do other than talk around here – and everyone does enough of that in the car.

Frontline volunteers come in a range of profiles and it’s difficult to paint them with a single brush. Many do indeed come from tough backgrounds and operate cowboy operations that don’t file paperwork – a huge detriment to the cause of their evacuees, who end up in resettlement zones hundreds of miles away from their homes with none of the promised services for internally displaced people lined up. That said, these people regularly risk their lives in places others won’t; whatever their reasons, they perform an important service. There are also the more buttoned-up crews – such as the one I have attached myself to – who are representative of so many of the people here who have sacrificed lives of relevant comfort for the cause. They tend to use their real names rather than call signs; one medic puts it bluntly that it’s easier to track someone down by name if they fuck you over. The rivalries between frontline ambulance services are stark, and unfortunately no organization has yet stepped in to unite them for common cause.

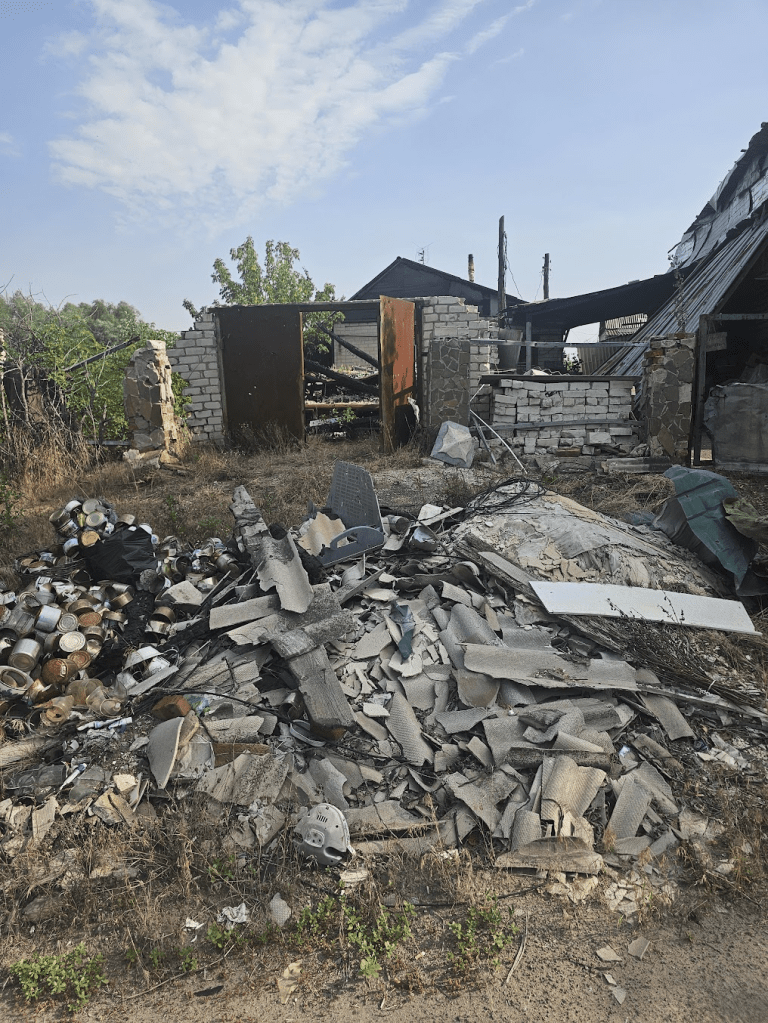

The rounds I attend are in the formerly occupied, now largely devastated city of Lyman – at this time around 15 kilometers from the front. The roads have been cleared, but they cut through heavily shelled and mined suburbs. One of the sights passed by is a youth summer camp a long way from future operations. A burned out vehicle on its side conveys a grave warning – “That wasn’t there last week,” says the doctor. Pavement gives way to dirt roads through neighborhoods of mostly destroyed buildings; even those still standing and occupied bear the scars of heavy damage. The dull thunder of explosions is unremitting; given the strategic importance of the area and the absence of air defenses, attacks are not just at any time – they simply do not stop.

One patient uses a mobility scooter – his second after Russian soldiers picked him off the street as he rode it. He was tortured for two weeks before he was pushed out again, scooterless. I don’t speak to him, but I’m told he has a “goofy” sense of humor.

Torture. It’s a word alien to the experience of people back home, so unfathomable is the distance a torturer feels from the people on whom they inflict pain. It is a regular practice for Russian soldiers, and it does not take speaking to too many people in Ukraine before you meet someone whose friend or family member was tortured to death. There is a deep frustration with American media, which reports every attack on Kyiv but not the continued violations of international law by soldiers fighting for Putin. Investigations by human rights lawyers have hit a funding wall, which is no surprise given how costly the analysis of evidence can be: Ukrainian dead are often returned as jumbled up parts in a body bag; an arm, a foot, a head if you’re lucky – all of these components from multiple people are often stuffed together into a single sack. There is no limit to a victim’s profile, and sexual violence is a feature of the experience for men and women alike. Soldiers at the front often reserve a “friendship grenade” for themselves in the event of imminent capture, while doctors close to the action will carry pentobarbital for the same purpose. Civilians are left without such recourse.

Though people grow used to the fear that flourishes in these parts, it does not go away; it wears and grinds on people who are subject to all of these horrors combined with the regular shelling aimed at dismantling any structure that can house Ukrainian defenses, block by block. Thus these people doing unglamorous work for no pay or recognition, of every description in appearance, present a sublime heroism that has not been surpassed in any age or any country. To walk amongst and speak with them is a humbling experience that I am grateful for, and I can only hope that the free people of the world are grateful for them as well.

* Save for a shashlik joint that’s locally beloved. For the uninitiated, shashlik is a Georgian barbecue style that, to the best of my palate’s appreciation, consists of enormous chunks of pork treated with heat. It’s a bit rudimentary, but also difficult to fuck up.

Leave a comment