Regards from Kharkiv.

I actually arrived yesterday, but after a journey spanning 4,900 miles (over 850 overland) and 60 hours spent between two cars, two planes, and three trains I needed to call an early night.

Putin’s invasion has rendered passenger air travel nonviable, and so the most practical method for non-official persons to traverse a county of over 223,000 square miles is by train. There is variable wisdom amongst regular travelers on this route over whether to go via Warsaw, Krakow, or Moldova; Krakow seems most popular. From Krakow, one takes the Polish intercity rail to Przemysl, near the Ukrainian border. There are two trains east from there every day and they are packed – mostly with women, but also a few children and men who stand over everyone like monoliths.

Some chatter, but most wait with resigned boredom for the immigration checkpoint to open. The Poles were smiley and solicitous towards me in my short time with them, and some even asked me for directions (they cut themselves short before my lips even completed their stretch to a sheepish, idiotic grin); meanwhile the Ukrainians just give me the occasional glance while I wonder if I stand in stark relief to the scene as a particularly gormless American.

Some will raise their eyes to mine and we will roll them in solidarity as the citizens of eastern Europe’s tech hub are forced to wait outside and unsheltered in a Polish border town.

I don’t mean to knock Przemysl (I will not tell you how to pronounce it), of course. The city traces its roots to the 8th century and has a population of 55,000 with a preserved historic center of its own. It is also one of five Polish municipalities that President Zelenskyy awarded as “Rescuer Cities” for services to Ukrainian refugees during the war. The conduct of Przemysl’s residents has been commendable.

Eventually, due to confusion in the queue, the man in front of me tries initiating a conversation in Ukrainian (maybe I blend in after all). After I helplessly stammer some apology, he calls to the people behind me for anyone who speaks English. That’s nobody, as it turns out, but two girls behind me know “follow me,” which works for now. They also know “where are you from,” but after I answer, they giggle, and we give a smiley nod to each other, discussion ends.

Passport control is a rapid formality, and I clamber into a train not of this century. At recommendation, I have opted for the “luxe” sleeping car – with padding.

My berth for the next 573 hours of my LIFE

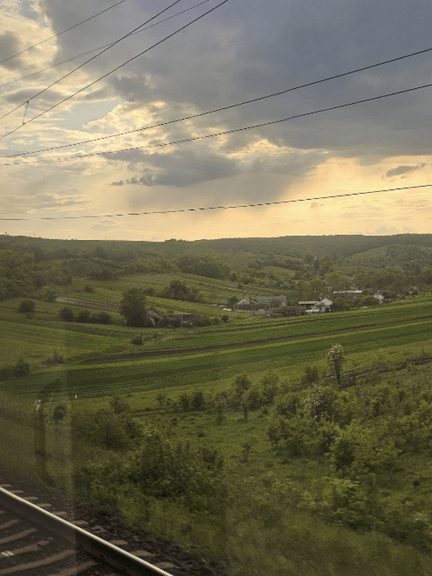

Looking out my compartment window as I drifted in and out, much Ukraine kind of looks like Pennsylvania: farms, forests, rolling hills, and small towns built around domed structures, while modern residential high rises mark denser populations. Occasionally you see remnants of unfinished developments and nature reclaiming aging vestiges of industry; Steelers would feel right at home.

On the road to Pittsburgh

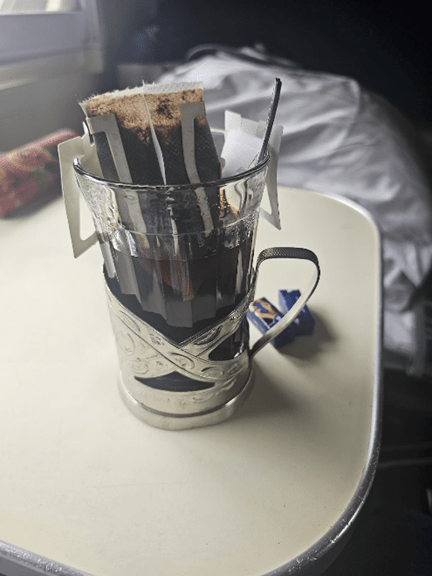

My roommate is a woman I estimate to be in her 60s named Luba, and we have some short interactions via the Google translate app. This carries some pitfalls, as evidenced by her advice to “cook” my passport; I’m still not sure what that means. Conversation is sparse, but considering the tightness of quarters, that may not be a bad thing. That said, both the train and my company have their charms: even without any English speakers, there is a refreshing air of humor and genuity. The coffee is good, too.

23 hours after my train from Psemysl left the station, I disembarked to a warm reception in an impressive city. Honestly, the ride wasn’t too bad. Slept a lot.

Kharkiv dates its incorporation to the 17th century, though most landmarks were built in the 20th. The buildings and parks are expansive and wonderfully well-kept, and my guide is suitably proud of his city and its presentation. Several governmental landmarks as well as civilian buildings bear the deep scars caused by Russian air attacks, but many of the damaged structures still stand in a show of resiliency.

Statues of Ukrainian symbols and luminaries have been covered in sandbags and wrapped, as Russian attackers have taken especial interest in targeting symbols of Ukrainian identity. This includes religious structures; the 17th century Assumption Cathedral was struck by missile fire in 2022.

Among the sights he takes me to is Freedom Square, which he proudly proclaims as the largest in Europe. Wikipedia says it’s actually in 8th, but it’s still quite impressive.

I take some time to refresh before going out again. A dinner at a Georgian restaurant and more than a few drinks later, I find myself right at the edge of the 11pm curfew. At this time, streetlights are put out to challenge target identification in the city (which of course has minimal impact on infrared-guided systems). The transformation of bustling streets to complete silence and darkness fills the air with an eerie sadness. Still, the stars stay visible on a clear night above Ukraine’s second-largest city, and a great orange moon rises as I make my way to my lodgings.

Leave a comment